A woman crammed in next to me apologised for pushing past and said: “Watch out for that guy in black, he just touched me and said, ‘You look good.’” New York was back, as they say. The bus lurched to a stop every two blocks and, after converging with the traffic on Broadway, ground to a complete halt. Someone else screamed to keep the doors open.

New york lockdown blackdown full#

The bus was full when it came, but we all shoved ourselves on.

The airlessness of lockdown, when no one could get away from their families, has been replaced with a sense of proximity to the city’s 8.5 million people, all of us trying to get to the same place, at the same time, on the same bus.Īfter school on Monday, I picked up my kids and we fought our way across Amsterdam Avenue to stand at the bus stop, where 15 other people milled around waiting. At street level, however, struggling for room on the pavement or an inch of space on the subway, it’s hard to avoid asking why we live like this. Those numbers crept up but, over an endless summer of few tourists and modest plans, the spell remained largely unbroken.įor businesses, Broadway, city finances and the rest, this September boom is welcome and necessary. New York shorn of visitors was a different, and in some ways easier, place to live, where, even at rush hour, you could time your movements around the city in increments of 10 minutes rather than hours.

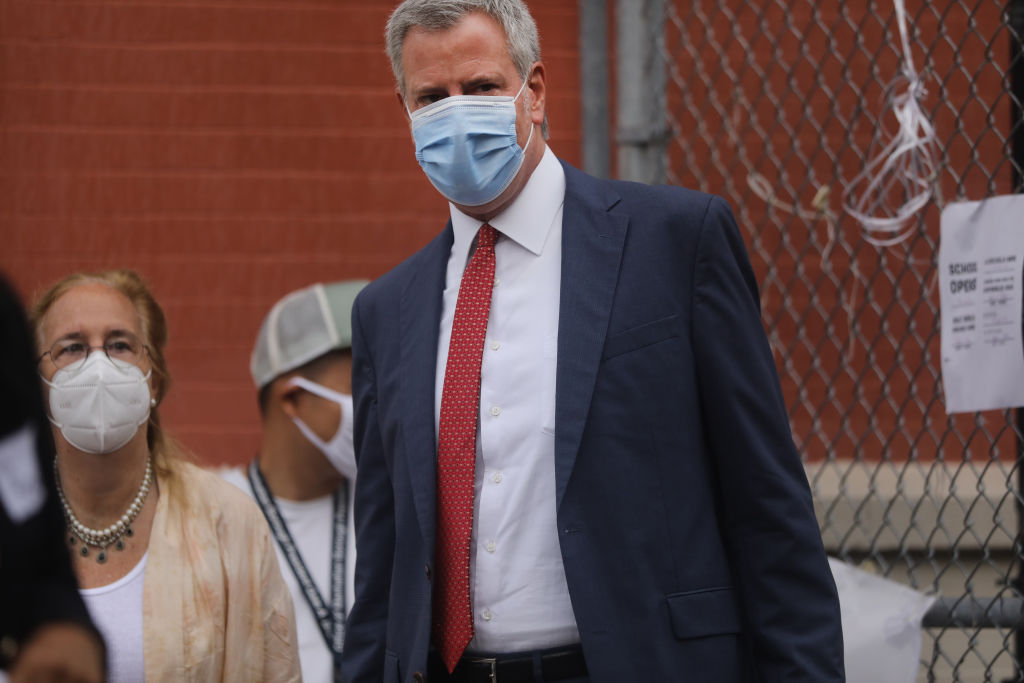

If lockdown brought on feelings of claustrophobia, these were offset by the bizarre – and there’s no denying it, thrilling – experience of living in an emptied-out city. Now that the place is jumping again, I realise that a much larger part of the experience had to do with the changed dynamics of the city. At the time I put it down, absurdly, to a combination of loyalty to the city, lack of opportunity to leave and, as I saw it, my own superior tolerance for discomfort. Unlike a lot of parents with young kids in the city, I never longed to move to the suburbs during those weeks of being cooped up in lockdown. The feeling was of an entire city on the move. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of public-sector workers in New York, ordered to return to in-person work, resumed the daily commute. School buses, back up to capacity, stood bumper to bumper. That first morning, parents, still prohibited from entering school buildings, lined up around the block to drop their children off at the gates. This was a good thing, putting an end to the split resources and scheduling nightmares of hybrid learning. Before the summer break, Bill de Blasio, the mayor of New York, announced that in September remote learning options would be retired the entire student body – with the exception of kids with particular health needs – would be required to turn up in person.

New york lockdown blackdown how to#

This Monday, the scene at the school gate felt like the resumption of a life many of us had forgotten how to lead. But it was still an unnerving, pared-down experience. Compared with full shutdown, it was a luxury, of course. In my children’s first-grade class there were fewer than 15 kids in attendance. For a year, children in the city who had opted for in-person learning – a mere 350,000 – had experienced a weird version of school, with some classes on Zoom and the vast majority of their classmates still learning remotely. In the largest school district in the US, the return looked, from a distance, vaguely normal. M ore than 1 million kids went back to school in New York this week.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)